Twice Born

The Death and Rebirth of Resettlement in Georgia

|

Dr. Tasha M. Hargrove, Dr. Robert Zabawa, and Ms. Michelle Pace

G.W.C. Experiment Station Tuskegee University A historical review of agriculture in Georgia from 1935-1938 reveals that one of the greatest struggles encountered by Blacks has been in the acquisition and retention of land. The acquisition and retention of land for Southern Blacks has meant something far more than economic viability. It has meant independence, security, self-sufficiency, self-reliance, and the opportunity to control one's own destiny.

|

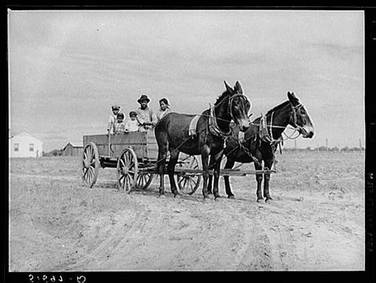

Prior to the Great Depression, the opportunity to own land in Georgia was limited for Blacks. During this time, the majority of Blacks earned their livelihood from the land; however, they were not landowners. Only 17% of Georgia Black farms were landowners at the turn of the Century in 1900. Thirty-five years later, this number had declined to 16%. The remaining 84% worked the land through the sharecropping and tenant farming system. The sharecropping system can best be described as a form of organized labor in which large, single-unit plantations were divided into smaller plots of land ranging from 30-to-50 acres each. The smaller plots of land "... were leased on a yearly basis to individual families, who operated as the primary unit of production. Each family at the end of the season received as compensation a share of the crop, usually one-third to one-half; sharecroppers were responsible for feeding and clothing themselves, while the landlord supplied all the farming provisions."

In most instances, the sharecropping system resulted in the exploitation of land and labor and left in its wake depleted soils. Sharecroppers were forced to work in an environment where they faced insurmountable difficulties - "...defective seed, poor livestock, lack of experience, outdated equipment and methods, and poor land." Poverty, illiteracy, and undernourishment were rampant during this period.

Simms (1983) summarized this historical era in Macon County, Georgia. She indicated "the degree of material progress in Macon County, and the limitations brought about by the depression, made Macon County in the 'thirties seem more aligned with Reconstruction days than the present era'. The prevailing philosophy had not undergone much alteration. Materially speaking, outdoor privies, wood stoves, well-drawn water, kerosene lamps, and dirt roads were some of the less romantic inconveniences that many Macon Countians of the 1930's shared with their 19th century predecessors."

Acquiring land in Georgia was difficult and there were many reasons why Blacks in Georgia did not own more of the land they worked. "In the beginning, few had capital to buy, and many factors worked to ensure that they did not accumulate the necessary money later. White supremacy, low cotton prices, and high interest rates kept the agricultural ladder from working. White farmers often refused to sell land to blacks, because it was more profitable to have it sharecropped; then they could rob the tenant of the fruits of their labor."

In an effort to elevate sharecroppers and tenant farmers into land ownership status and to alleviate poverty in rural areas, the United States government, under the leadership of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, initiated one of the most innovative, experimental land reform programs in U.S. history. Once twice - in U.S. history, once during Emancipation and again during the Reconstruction Era, had the U.S. government devised and implemented programs aimed at strengthening the land-owning capacities of Black farmers. Roosevelt's programs were implemented under the United States Department of Agriculture Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration, and were part of the New Deal Programs. New Deal Programs were aimed at "...transforming a depressed class of agricultural tenants and laborers into viable communities of small farmers and entrepreneurs."

Raper (1936) in his assessment of the New Deal Program indicated, "the New Deal with its cotton restriction program, its relief expenditures, and its loan services, has temporarily revitalized the Black Belt, and has rejuvenated the decaying plantation economy."

The Resettlement Administration purchased approximately 1,865,000 acres of land in almost 200 locales across the country and established a series of supervised farming and industrial communities. Thirteen of these resettlement communities were designated for Black farmers in the South. These all-Black communities encompassed 1,150 families on 92,000 acres of land. One of the 13 all-Black communities established by the New Deal Resettlement Administration was Flint River Farms in Montezuma, Georgia.

The evolution of the Flint River Farms project began in Fort Valley, Georgia in 1935 when A.T. Wilson, Chairman of the Local Resettlement Communities and Representative of The Fort Valley Normal and Industrial School, wrote a letter to the Division of Rural Resettlement in Washington, DC. requesting that a 6,000 acre project be located in rural Georgia. Harry Brown, Director of the Agricultural Extension Service, supported this request and believed that Fort Valley, which was located in Peach County, Georgia, represented the ideal setting for this type of project. Mr. Brown outlined several advantages for locating the project in Peach County. He stated "the first of these advantages and a very important one, is the fact that there is an excellent Negro school at Fort Valley which is doing high class work both from an academic and vocational agriculture point of view...The Agricultural Extension Service point of view there is a distinct advantage in this location represented by the fact that we have a good Negro county agent who has had a long period of satisfactory service in this section. We also have a Negro home demonstration agent carrying on a good program in that county."

In July 1936, Fort Valley Farms was authorized and approved. The plans for the project included 75 farms that would be 50 acres and 25 farms that would be approximately 70 acres. Fort Valley Farm plans included a community building that would have 12 class rooms, an auditorium and stage, a health room, library, home economics and community kitchen; a shop and a forge, and principal's office. Plans also called for a vocational training/agricultural teacher, home economics teacher, and a nurse.

The Fort Valley Farms Project never came to fruition. Due to unfavorable sentiments in the community and local opposition from White citizens, the Fort Valley farms project was cancelled. The opposition came in the form of petitions circulated throughout Peach County to reject the project. Only a few citizens opposed the Resettlement project and they protested by petitioning and addressing local and national officials. In November 1936, approval was given for the Fort Valley Farms project to be moved to the town of Montezuma in adjacent Macon County. Before the project plans were finalized in Macon County, there was once again opposition. The concerns were expressed by a few but highly vocal citizens through letters and petitions. Their stated concerns were: (1) land values would depreciate; (2) the government would purchased very little locally; (3) land would be taken off the tax roles; (4) the segregation of 100 Negro families would be abnormal and contrary to anything known in the South for years, (5) Negroes whose applications were turned down would be dissatisfied and feel they had been discriminated against; (6) if the project was successful Negroes working on surrounding farms would be dissatisfied with wages from private landowners; and (7) if the project was unsuccessful, then it would be a waste of government money and 100 Negro families would be demoralized.

Although there were approximately 450 citizens that signed the petitions, many were influenced and tricked into signing. Despite local opposition, on May 8, 1937 the name of Fort Valley Farms was changed to Flint River Farms and the project was officially moved to Macon County, Georgia.

Flint River Farms was sorely needed to establish a land owning class of Black farmers. By 1935, only 11% of the Black farmers in Macon County farmed on any owned land (And only 8% were full owners), while the vast majority (89%) were sharecroppers, tenants, or managers.

In most instances, the sharecropping system resulted in the exploitation of land and labor and left in its wake depleted soils. Sharecroppers were forced to work in an environment where they faced insurmountable difficulties - "...defective seed, poor livestock, lack of experience, outdated equipment and methods, and poor land." Poverty, illiteracy, and undernourishment were rampant during this period.

Simms (1983) summarized this historical era in Macon County, Georgia. She indicated "the degree of material progress in Macon County, and the limitations brought about by the depression, made Macon County in the 'thirties seem more aligned with Reconstruction days than the present era'. The prevailing philosophy had not undergone much alteration. Materially speaking, outdoor privies, wood stoves, well-drawn water, kerosene lamps, and dirt roads were some of the less romantic inconveniences that many Macon Countians of the 1930's shared with their 19th century predecessors."

Acquiring land in Georgia was difficult and there were many reasons why Blacks in Georgia did not own more of the land they worked. "In the beginning, few had capital to buy, and many factors worked to ensure that they did not accumulate the necessary money later. White supremacy, low cotton prices, and high interest rates kept the agricultural ladder from working. White farmers often refused to sell land to blacks, because it was more profitable to have it sharecropped; then they could rob the tenant of the fruits of their labor."

In an effort to elevate sharecroppers and tenant farmers into land ownership status and to alleviate poverty in rural areas, the United States government, under the leadership of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, initiated one of the most innovative, experimental land reform programs in U.S. history. Once twice - in U.S. history, once during Emancipation and again during the Reconstruction Era, had the U.S. government devised and implemented programs aimed at strengthening the land-owning capacities of Black farmers. Roosevelt's programs were implemented under the United States Department of Agriculture Resettlement Administration and its successor, the Farm Security Administration, and were part of the New Deal Programs. New Deal Programs were aimed at "...transforming a depressed class of agricultural tenants and laborers into viable communities of small farmers and entrepreneurs."

Raper (1936) in his assessment of the New Deal Program indicated, "the New Deal with its cotton restriction program, its relief expenditures, and its loan services, has temporarily revitalized the Black Belt, and has rejuvenated the decaying plantation economy."

The Resettlement Administration purchased approximately 1,865,000 acres of land in almost 200 locales across the country and established a series of supervised farming and industrial communities. Thirteen of these resettlement communities were designated for Black farmers in the South. These all-Black communities encompassed 1,150 families on 92,000 acres of land. One of the 13 all-Black communities established by the New Deal Resettlement Administration was Flint River Farms in Montezuma, Georgia.

The evolution of the Flint River Farms project began in Fort Valley, Georgia in 1935 when A.T. Wilson, Chairman of the Local Resettlement Communities and Representative of The Fort Valley Normal and Industrial School, wrote a letter to the Division of Rural Resettlement in Washington, DC. requesting that a 6,000 acre project be located in rural Georgia. Harry Brown, Director of the Agricultural Extension Service, supported this request and believed that Fort Valley, which was located in Peach County, Georgia, represented the ideal setting for this type of project. Mr. Brown outlined several advantages for locating the project in Peach County. He stated "the first of these advantages and a very important one, is the fact that there is an excellent Negro school at Fort Valley which is doing high class work both from an academic and vocational agriculture point of view...The Agricultural Extension Service point of view there is a distinct advantage in this location represented by the fact that we have a good Negro county agent who has had a long period of satisfactory service in this section. We also have a Negro home demonstration agent carrying on a good program in that county."

In July 1936, Fort Valley Farms was authorized and approved. The plans for the project included 75 farms that would be 50 acres and 25 farms that would be approximately 70 acres. Fort Valley Farm plans included a community building that would have 12 class rooms, an auditorium and stage, a health room, library, home economics and community kitchen; a shop and a forge, and principal's office. Plans also called for a vocational training/agricultural teacher, home economics teacher, and a nurse.

The Fort Valley Farms Project never came to fruition. Due to unfavorable sentiments in the community and local opposition from White citizens, the Fort Valley farms project was cancelled. The opposition came in the form of petitions circulated throughout Peach County to reject the project. Only a few citizens opposed the Resettlement project and they protested by petitioning and addressing local and national officials. In November 1936, approval was given for the Fort Valley Farms project to be moved to the town of Montezuma in adjacent Macon County. Before the project plans were finalized in Macon County, there was once again opposition. The concerns were expressed by a few but highly vocal citizens through letters and petitions. Their stated concerns were: (1) land values would depreciate; (2) the government would purchased very little locally; (3) land would be taken off the tax roles; (4) the segregation of 100 Negro families would be abnormal and contrary to anything known in the South for years, (5) Negroes whose applications were turned down would be dissatisfied and feel they had been discriminated against; (6) if the project was successful Negroes working on surrounding farms would be dissatisfied with wages from private landowners; and (7) if the project was unsuccessful, then it would be a waste of government money and 100 Negro families would be demoralized.

Although there were approximately 450 citizens that signed the petitions, many were influenced and tricked into signing. Despite local opposition, on May 8, 1937 the name of Fort Valley Farms was changed to Flint River Farms and the project was officially moved to Macon County, Georgia.

Flint River Farms was sorely needed to establish a land owning class of Black farmers. By 1935, only 11% of the Black farmers in Macon County farmed on any owned land (And only 8% were full owners), while the vast majority (89%) were sharecroppers, tenants, or managers.

All research activities were funded through the United States Department of Agriculture's 1890 Institution Capacity Building Grant (2001-38814-11436) "Assessing Government Partnerships in Rural Community Development" awarded to Tuskegee University. The Tuskegee University Research Team included Dr. Robert Zabawa, Principal Investigator, Dr. Ntam Baharanyi, Principal Investigator, Dr. Tasha Hargrove, Research Assistant Professor, Ms. Alice Paris, Project Coordinator, and Ms. Michelle Pace, Graduate Student.